This strip is also up on on Design Week!

Know someone who might enjoy this comic? Help spread the word and share this with them! I need all the help I can get… THANK YOU!

For paying subscribers, today’s post also comes with extra stuff! Fridays are when I sometimes ramble on about random things, share behind the scenes stuff, show WIP versions of future strips, chat about other projects i’m working on, or dredge up some old stuff from my cartooning past. You also get some music recommendations and can claim your own DT! avatar. Why not upgrade and join us?

Transcript

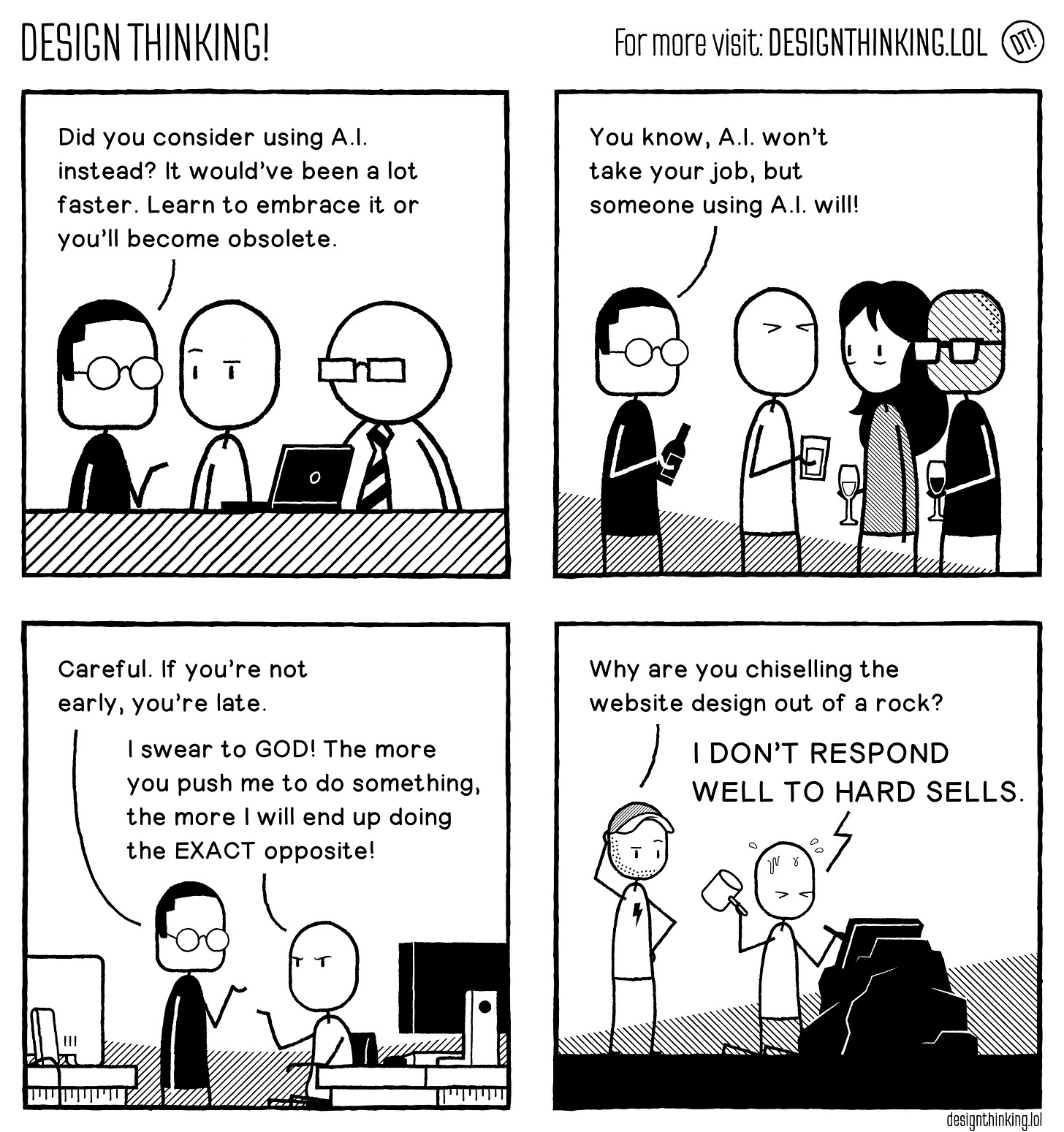

A comic strip in four panels:

-

An adventurer kneels on a path, facing a small cookie with tiny arms and legs. The creature looks miserable and is crying while looking at the ground. The adventurer is concerned for the little being.

Adventurer: Oh... What’s wrong, my little fellow?

-

Close-up of the little cookie lifting its head, eyes still teary.

Cookie: Well, I’m a little cookie, but no one accepts me anymore...

-

With a kind heart and to comfort it, the adventurer picks it up in her hand and says in a motherly tone.

Adventurer: Come on, I accept you. Climb onto my back.

-

Wide shot of the path, our adventurer with the little cookie on her shoulder walking towards the horizon, both happy with their encounter. In the foreground, among the grass at the edge of the path, a small army of fierce cookies with camouflage makeup emerges. Their leader whispers the order:

Cookie Leader: Alright, guys, she took the bait! Let’s track her down!

What’s a good maximum line length for your coding standard?

This is, of course, a trick question. By posing it as a question, I have created the misleading impression that it is a question, but Black has selected the correct number for you; it’s 88 which is obviously very lucky.

Thanks for reading my blog.

OK, OK. Clearly, there’s more to it than that. This is an age-old debate on the level of “tabs versus spaces”. So contentious, in fact, that even the famously opinionated Black does in fact let you change it.

Ancient History

One argument that certain silly people1 like to make is “why are we wrapping at 80 characters like we are using 80 character teletypes, it’s the 2020s! I have an ultrawide monitor!”. The implication here is that the width of 80-character terminals is an antiquated relic, based entirely around the hardware limitations of a bygone era, and modern displays can put tons of stuff on one line, so why not use that capability?

This feels intuitively true, given the huge disparity between ancient times and now: on my own display, I can comfortably fit about 350 characters on a line. What a shame, to have so much room for so many characters in each line, and to waste it all on blank space!

But... is that true?

I stretched out my editor window all the way to measure that ‘350’ number, but I did not continue editing at that window width. In order to have a more comfortable editing experience, I switched back into writeroom mode, a mode which emulates a considerably more writerly application, which limits each line length to 92 characters, regardless of frame width.

You’ve probably noticed this too. Almost all sites that display prose of any kind limit their width, even on very wide screens.

As silly as that tiny little ribbon of text running down the middle of your monitor might look with a full-screened stereotypical news site or blog, if you full-screen a site that doesn’t set that width-limit, although it makes sense that you can now use all that space up, it will look extremely, almost unreadably bad.

Blogging software does not set a column width limit on your text because of some 80-character-wide accident of history in the form of a hardware terminal.

Similarly, if you really try to use that screen real estate to its fullest for coding, and start editing 200-300 character lines, you’ll quickly notice it starts to feel just a bit weird and confusing. It gets surprisingly easy to lose your place. Rhetorically the “80 characters is just because of dinosaur technology! Use all those ultrawide pixels!” talking point is quite popular, but practically people usually just want a few more characters worth of breathing room, maxing out at 100 characters, far narrower than even the most svelte widescreen.

So maybe those 80 character terminals are holding us back a little bit, but... wait a second. Why were the terminals 80 characters wide in the first place?

Ancienter History

As this lovely Software Engineering Stack Exchange post summarizes, terminals were probably 80 characters because teletypes were 80 characters, and teletypes were probably 80 characters because punch cards were 80 characters, and punch cards were probably 80 characters because that’s just about how many typewritten characters fit onto one line of a US-Letter piece of paper.

Even before typewriters, consider the average newspaper: why do we call a regularly-occurring featured article in a newspaper a “column”? Because broadsheet papers were too wide to have only a single column; they would always be broken into multiple! Far more aggressive than 80 characters, columns in newspapers typically have 30 characters per line.

The first newspaper printing machines were custom designed and could have used whatever width they wanted, so why standardize on something so narrow?3

Science!

There has been a surprising amount of scientific research around this issue, but in brief, there’s a reason here rooted in human physiology: when you read a block of text, you are not consciously moving your eyes from word to word like you’re dragging a mouse cursor, repositioning continuously. Human eyes reading text move in quick bursts of rotation called “saccades”. In order to quickly and accurately move from one line of text to another, the start of the next line needs to be clearly visible in the reader’s peripheral vision in order for them to accurately target it. This limits the angle of rotation that the reader can perform in a single saccade, and, thus, the length of a line that they can comfortably read without hunting around for the start of the next line every time they get to the end.

So, 80 (or 88) characters isn’t too unreasonable for a limit. It’s longer than 30 characters, that’s for sure!

But, surely that’s not all, or this wouldn’t be so contentious in the first place?

Caveats

The screen is wide, though.

The ultrawide aficionados do have a point, even if it’s not really the simple one about “old terminals” they originally thought. Our modern wide-screen displays are criminally underutilized, particularly for text. Even adding in the big chunky file, class, and method tree browser over on the left and the source code preview on the right, a brief survey of a Google Image search for “vs code” shows a lot of editors open with huge, blank areas on the right side of the window.

Big screens are super useful as they allow us to leverage our spatial memories to keep more relevant code around and simply glance around as we think, rather than navigate interactively. But it only works if you remember to do it.

Newspapers allowed us to read a ton of information in one sitting with minimum shuffling by packing in as much as 6 columns of text. You could read a column to the bottom of the page, back to the top, and down again, several times.

Similarly, books fill both of their opposed pages with text at the same time, doubling the amount of stuff you can read at once before needing to turn the page.

You may notice that reading text in a book, even in an ebook app, is more comfortable than reading a ton of text by scrolling around in a web browser. That’s because our eyes are built for saccades, and repeatedly tracking the continuous smooth motion of the page as it scrolls to a stop, then re-targeting the new fixed location to start saccading around from, is literally more physically strenuous on your eye’s muscles!

There’s a reason that the codex was a big technological innovation over the scroll. This is a regression!

Today, the right thing to do here is to make use of horizontally split panes in your text editor or IDE, and just make a bit of conscious effort to set up the appropriate code on screen for the problem you’re working on. However, this is a potential area for different IDEs to really differentiate themselves, and build multi-column continuous-code-reading layouts that allow for buffers to wrap and be navigable newspaper-style.

Similar, modern CSS has shockingly good support for multi-column layouts, and it’s a shame that true multi-column, page-turning layouts are so rare. If I ever figure out a way to deploy this here that isn’t horribly clunky and fighting modern platform conventions like “scrolling horizontally is substantially more annoying and inconsistent than scrolling vertically” maybe I will experiment with such a layout on this blog one day. Until then… just make the browser window narrower so other useful stuff can be in the other parts of the screen, I guess.

Code Isn’t Prose

But, I digress. While I think that columnar layouts for reading prose are an interesting thing more people should experiment with, code isn’t prose.

The metric used for ideal line width, which you may have noticed if you clicked through some of those Wikipedia links earlier, is not “character cells in your editor window”, it is characters per line, or “CPL”.

With an optimal CPL somewhere between 45 and 95, a code-line-width of somewhere around 90 might actually be the best idea, because whitespace uses up your line-width budget. In a typical object-oriented Python program2, most of your code ends up indented by at least 8 spaces: 4 for the class scope, 4 for the method scope. Most likely a lot of it is 12, because any interesting code will have at least one conditional or loop. So, by the time you’re done wasting all that horizontal space, a max line length of 90 actually looks more like a maximum of 78... right about that sweet spot from the US-Letter page in the typewriter that we started with.

What about soft-wrap?

In principle, source code is structured information, whose presentation could be fully decoupled from its serialized representation. Everyone could configure their preferred line width appropriate to their custom preferences and the specific physiological characteristics of their eyes, and the code could be formatted according to the language it was expressed in, and “hard wrapping” could be a silly antiquated thing.

The problem with this argument is the same as the argument against “but tabs are semantic indentation”, to wit: nope, no it isn’t. What “in principle” means in the previous paragraph is actually “in a fantasy world which we do not inhabit”. I’d love it if editors treated code this way and we had a rich history and tradition of structured manipulations rather than typing in strings of symbols to construct source code textually. But that is not the world we live in. Hard wrapping is unfortunately necessary to integrate with diff tools.

So what’s the optimal line width?

The exact, specific number here is still ultimately a matter of personal preference.

Hopefully, understanding the long history, science, and underlying physical constraints can lead you to select a contextually appropriate value for your own purposes that will balance ease of reading, integration with the relevant tools in your ecosystem, diff size, presentation in the editors and IDEs that your contributors tend to use, reasonable display in web contexts, on presentation slides, and so on.

But — and this is important — counterpoint:

No it isn’t, you don’t need to select an optimal width, because it’s already been selected for you. It is 88.

Acknowledgments

Thank you for reading, and especially thank you to my patrons who are supporting my writing on this blog. If you like what you’ve read here and you’d like to read more of it, or you’d like to support my various open-source endeavors, you can support my work as a sponsor!

-

I love the fact that this message is, itself, hard-wrapped to 77 characters. ↩

-

Let’s be honest; we’re all object-oriented python programmers here, aren’t we? ↩

-

Unsurprisingly, there are also financial reasons. More, narrower columns meant it was easier to fix typesetting errors and to insert more advertisements as necessary. But readability really did have a lot to do with it, too; scientists were looking at ease of reading as far back as the 1800s. ↩

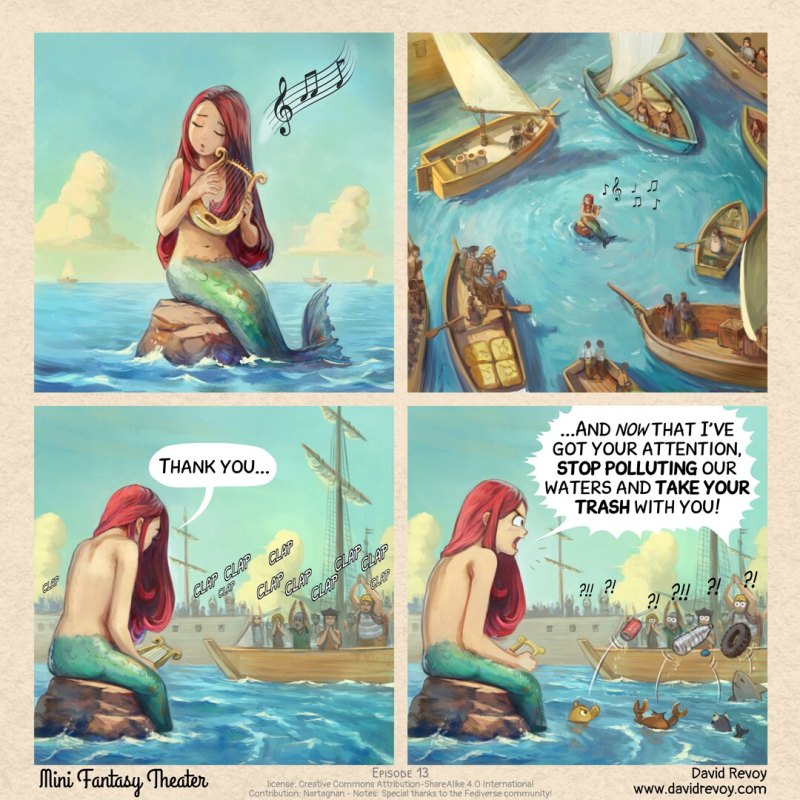

Transcript:

A webcomic storyboard in four panels, black and white and sketchy:

Panel 1: A cute mermaid sings, eyes closed, with a melancholy expression, sitting on a rock in the middle of the ocean. She plays a small lyre.

Panel 2: Aerial view: many boats gather, forming a circle around the mermaid, drawn in by her performance.

Panel 3: The mermaid bows modestly to the enthusiastic applause of the sailors on the boats, who give her a standing ovation.

Mermaid: Thank you...

Panel 4. The mermaid now yell angrily to the sailors. In the foreground little fish, crab, and shark are throwing trash back to the boats.

Mermaid: "...And now that I've got your attention, stop polluting our waters and take your trash with you!"

(Source soon on peppercarrot.com, Friday, I'm travelling right now)

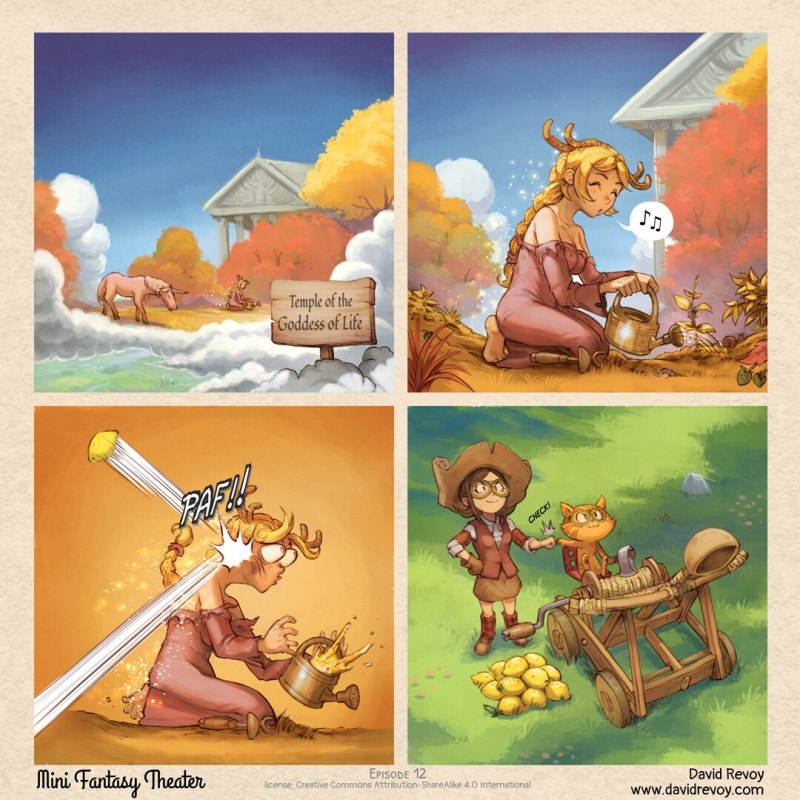

Transcript:

A comic comic in four panels:

Panel 1: A landscape view of a temple floating above the clouds. The landscape is colored with golden and purple hues, which are unusual for the land of mortals. In the foreground, a sign reads, "Temple of the Goddess of Life."

Panel 2: The Goddess of Life kneels in her garden, watering it while whistling. She is happy and enjoying her peaceful daily routine.

Panel 3: Suddenly, the Goddess of Life is violently punched in the face by a flying lemon coming from below the clouds.

Panel 4: A top-down view of a catapult with lemons. Pepper, a young witch, and her cat, Carrot, are in command. They bump fists in a "Check!" sound while watching the sky with fierce eyes.